Health Inequities are systematic differences in the health status of different population groups. These health inequities have significant social and economic costs both to individuals and societies (WHO, 2018).

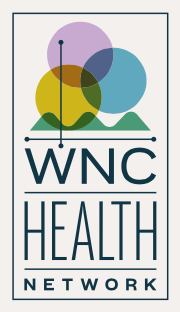

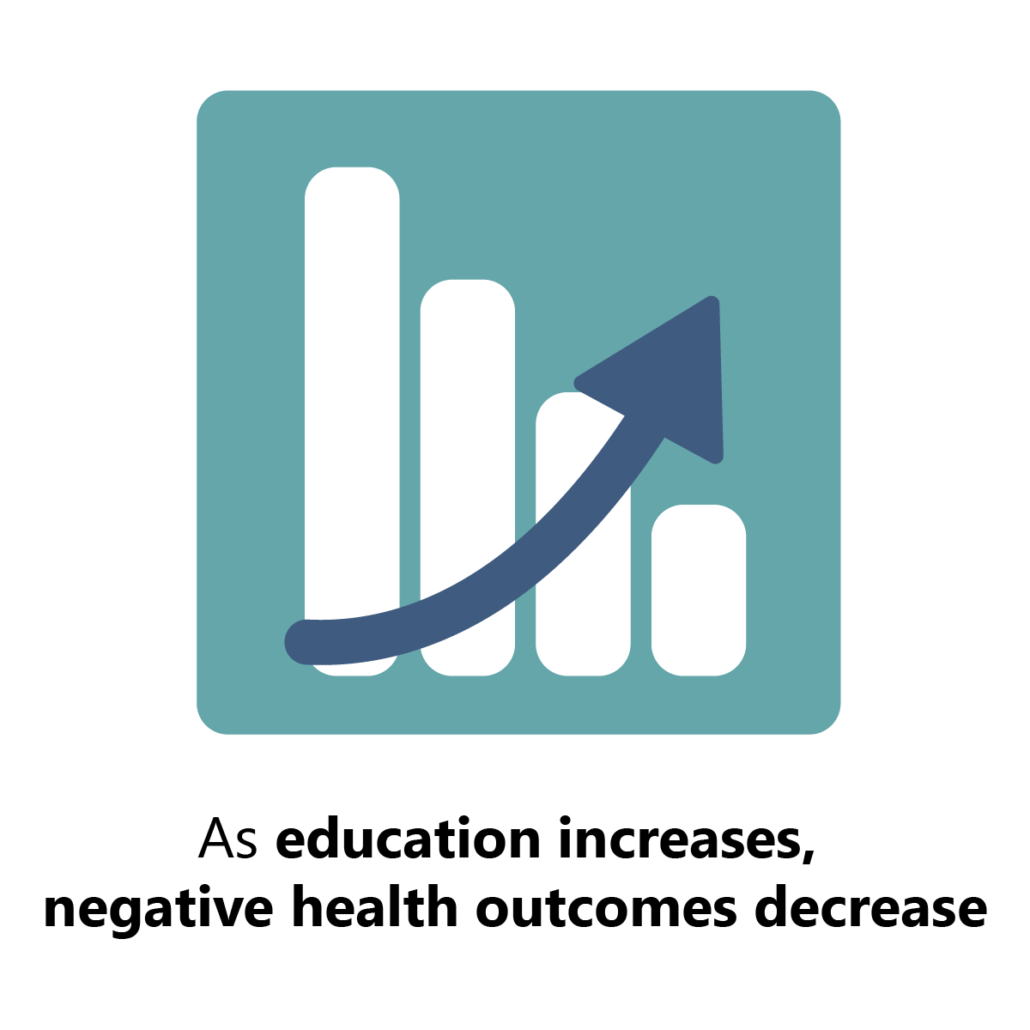

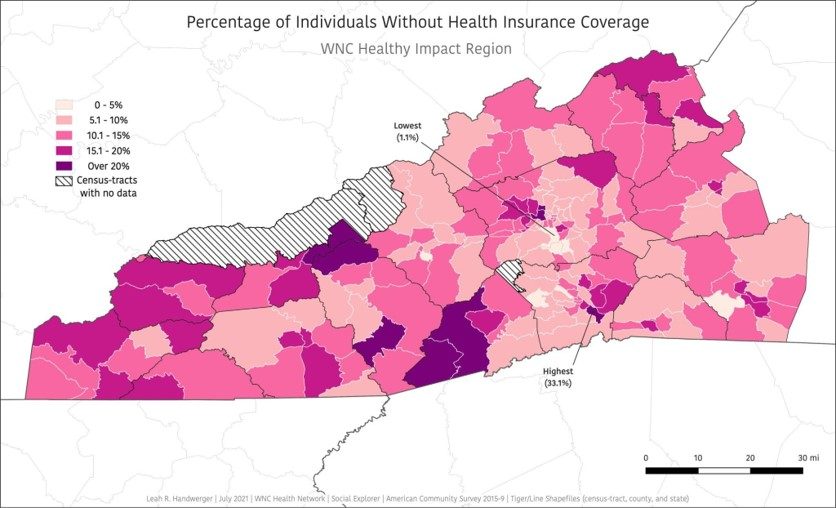

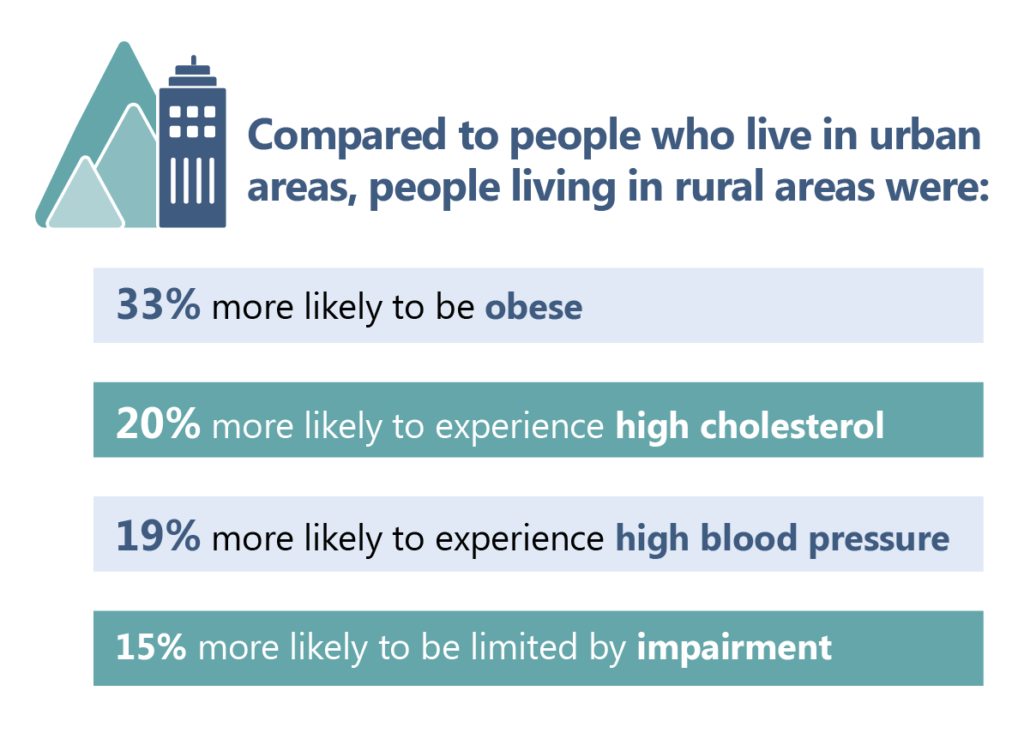

The following key social determinants of health were found to be strongly correlated with poorer health conditions and health outcomes in western North Carolina: lower income status, lower levels of educational attainment, unemployment, being uninsured, residing in a rural area, and identifying as certain races/ethnicities (WNCHN, 2023).

For the following analysis, datasets from the regional survey were analyzed for the years 2012, 2015, and 2018 for all 16 counties in the region. All analysis accounted for the complex survey design and used sample survey weights. Adjusted and unadjusted logistic regression models were used to examine the association between health outcomes and a number of demographic characteristics and social determinants of health. Analysis used pooled data across survey years when possible for each outcome of interests (2012-2018). Due to limitations in the population size and demographics of western North Carolina, data cannot be disaggregated by county or demographic characteristics further.